Switch terms are a concept that is often misunderstood in vector network analyzers (VNAs). Although they are essential for VNA calibration, VNA vendors rarely discuss them in their user manuals. Unlike S-parameters, switch terms cannot be directly selected and displayed on a VNA; instead, they must be defined using wave parameters.

The purpose of this post is to help you understand the physical meaning of switch terms, explain what they are, and show you how the math is defined. Additionally, I will show you a technique for indirectly measuring switch terms from the VNA using a couple of reciprocal devices [1]. For sample measurements and Python scripts, check my GitHub repository: https://github.com/ZiadHatab/vna-switch-terms

Physical Meaning

To understand the concept of switch terms, let’s start with the basic definition of S-parameters. S-parameters describe a linear transformation between incident and reflected waves, which can be represented by the following matrix equation:

\[\begin{bmatrix} \hat{b}_{1}\\\hat{b}_{2} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} S_{11} & S_{12}\\ S_{21} & S_{22} \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} \hat{a}_{1}\\\hat{a}_{2} \end{bmatrix} \label{eq:1}\]where $\hat{a}_i$ and $\hat{b}_i$ represent the incident and reflected waves at port-i, respectively. We can expand this matrix notation into two equations:

\[\hat{b}_1 = S_{11}\hat{a}_1 + S_{12}\hat{a}_2, \qquad \hat{b}_2 = S_{21}\hat{a}_1 + S_{22}\hat{a}_2 \label{eq:2}\]The most common way to solve for S-parameters, and how they are often taught, is to set one incident wave to zero and express each S-parameter as a ratio:

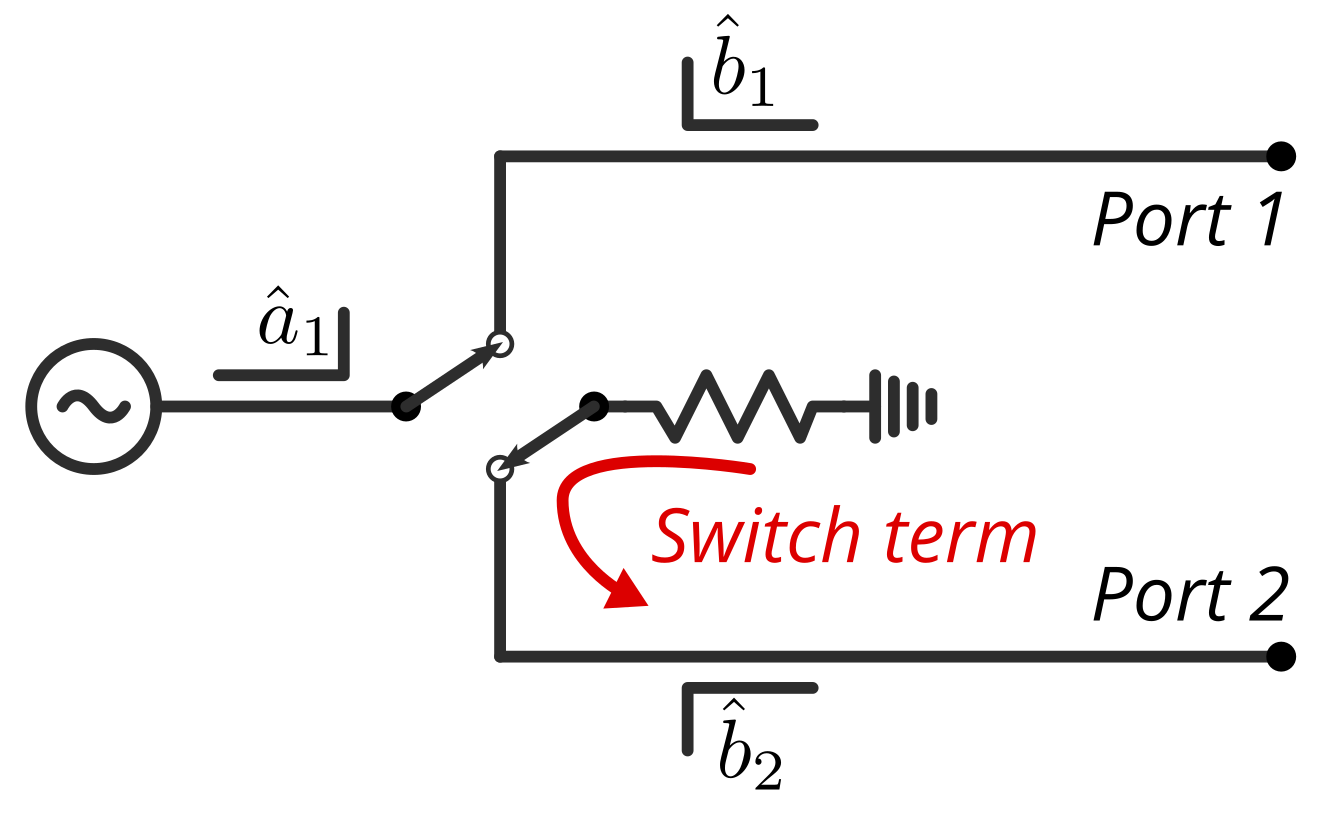

\[S_{11} = \left. \frac{\hat{b}_1}{\hat{a}_1}\right|_{\hat{a}_2=0}, \qquad S_{12} = \left. \frac{\hat{b}_1}{\hat{a}_2}\right|_{\hat{a}_1=0}, \qquad S_{21} = \left. \frac{\hat{b}_2}{\hat{a}_1}\right|_{\hat{a}_2=0}, \qquad S_{22} = \left. \frac{\hat{b}_2}{\hat{a}_2}\right|_{\hat{a}_1=0} \label{eq:3}\]In reality, it is not possible to set the incident wave of the opposite port to zero. Even if you turn off the source at the other port, energy exiting the DUT can reflect back and re-enter it. From the DUT’s perspective, this reflected energy is an incident wave. Therefore, the assumption $\hat{a}_2 = 0$ for computing $S_{11}$, for example, does not hold in practice. See the illustration below.

Fig. 1. Illustration of exciting wave at port-1 for a two-port DUT.

Fig. 1. Illustration of exciting wave at port-1 for a two-port DUT.

Teaching S-parameters this way can be misleading, as these conditions are not achievable in practice. Even hobbyist VNAs like the NanoVNA display a backplate diagram that assumes the incident wave at the second port is zero. Of course, good impedance matching is always desirable, but perfect matching is simply not achievable at all frequencies.

Fig. 2. NanoVNA backplate diagram of measurement concept.

Fig. 2. NanoVNA backplate diagram of measurement concept.

The reflection at the non-driving port is what we call the switch term. The name may seem puzzling, as we haven’t talked about switches yet, but the key point is that the incident wave at the non-driving port is directly related to the switch term.

The name “switch term” comes from how VNAs are typically built. Many VNAs use an electronic switch to flip between ports, driving one port at a time while the others are terminated, usually by the switch itself. Because the reflection arises from a mismatch in that termination, the term “switch term” was coined. You can read more about the origin of this name in [2].

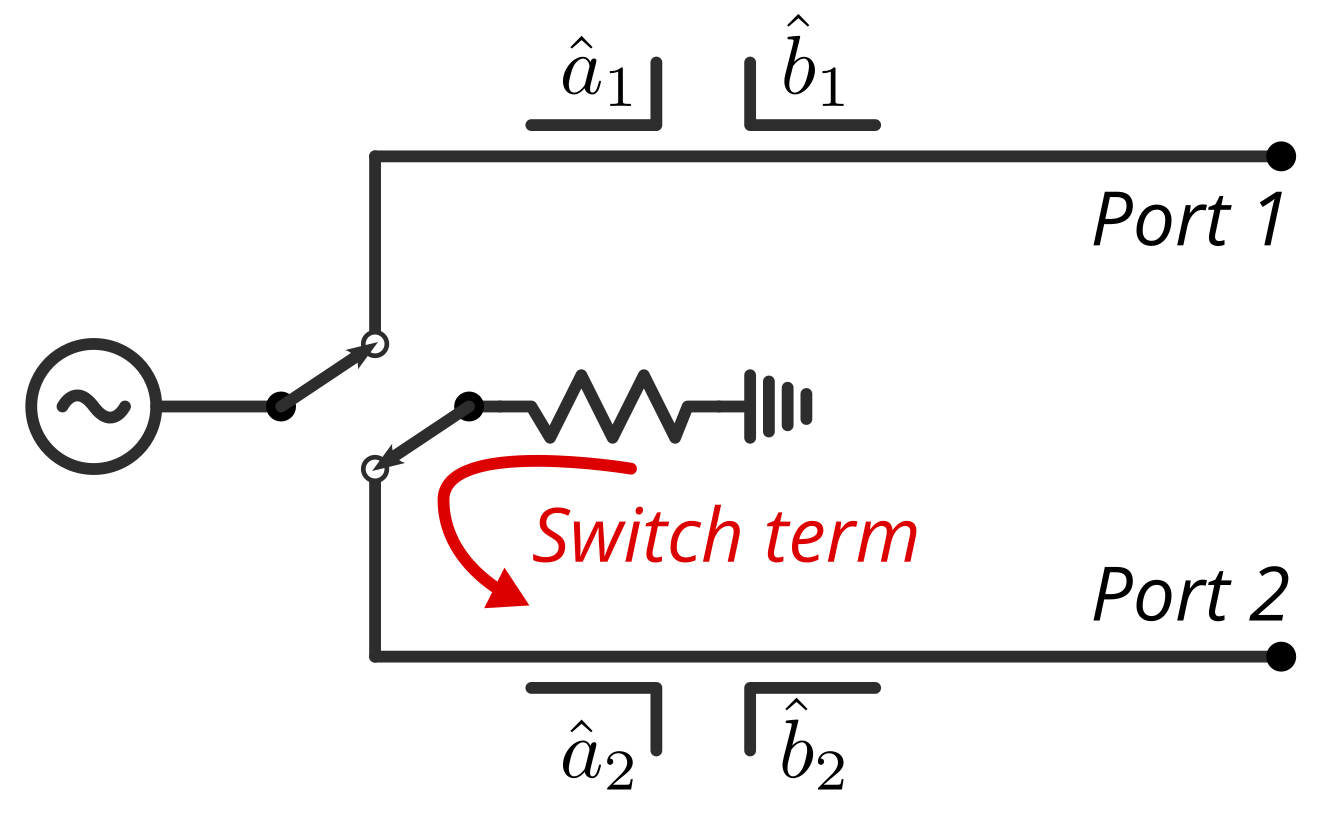

The illustration below shows the two most common VNA architecture designs. On the left is the three-sampler approach, where a common receiver is used to sample the incident wave of the source and two receivers for reflections. The three-sampler design is often used in low-cost VNAs and in older designs. However, most new VNAs use a four-sampler design, where every port gets two receivers. With a four-sampler VNA, we can sample the incident wave of the source and termination (i.e., switch term). Keep in mind that for an N-port VNA, there are N switch terms.

Direct Measurement

This section explains how S-parameters are formally defined and where switch terms arise. The focus is on two-port VNAs, with the N-port generalization given at the end.

In a two-port VNA, waves are sampled twice: once in the forward direction, driven by port-1, and once in the reverse direction, driven by port-2. Therefore, we have two sets of equations:

\[\begin{bmatrix} \hat{b}_{11}\\\hat{b}_{21} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} S_{11} & S_{12}\\ S_{21} & S_{22} \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} \hat{a}_{11}\\\hat{a}_{21} \end{bmatrix}, \qquad \begin{bmatrix} \hat{b}_{12}\\\hat{b}_{22} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} S_{11} & S_{12}\\ S_{21} & S_{22} \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} \hat{a}_{12}\\\hat{a}_{22} \end{bmatrix} \label{eq:4}\]where $\hat{a}_{ij}$ and $\hat{b}_{ij}$ represent the sampled incident and reflected waves, respectively, at port-i when driven by port-j. In the above notation, the S-parameters are the same whether the VNA is driving from port-1 or port-2, as the DUT remains constant. We can combine both results into a single matrix:

\[\begin{bmatrix} \hat{b}_{11} & \hat{b}_{12}\\ \hat{b}_{21} & \hat{b}_{22} \end{bmatrix} = \underbrace{\begin{bmatrix} S_{11} & S_{12}\\ S_{21} & S_{22} \end{bmatrix}}_{\bs{S}}\begin{bmatrix} \hat{a}_{11} & \hat{a}_{12}\\ \hat{a}_{21} & \hat{a}_{22} \end{bmatrix} \label{eq:5}\]The above expression presents the correct way to calculate S-parameters. If you are using a four-sampler VNA, you can measure all eight waves. Therefore, you can simply take the inverse of the matrix containing the incident waves to obtain the S-parameters. The definition presented here already accounts for switch terms and can be extended to any number of ports.

Returning to switch terms: they remain relevant because most two-port VNAs ship with four receivers but intentionally use only three, never sampling the incident wave of the non-driving port. The most likely reason is backward compatibility with older three-receiver designs, or simply to reduce buffer memory usage. The fourth receiver is still used, but only once, to measure the switch terms themselves during calibration, since they are deterministic and can be reused.

In a three-sampler VNA, the waves $\hat{a}_{12}$ and $\hat{a}_{21}$ are not measured due to a lack of dedicated receivers. In a four-sampler VNA, they are intentionally not measured. To address this, the matrix of measured incident waves in the above equation can be split into two matrices, as shown below:

\[\begin{bmatrix} \hat{b}_{11} & \hat{b}_{12}\\ \hat{b}_{21} & \hat{b}_{22} \end{bmatrix} = \bs{S}\begin{bmatrix} 1 & \frac{\hat{a}_{12}}{\hat{a}_{22}}\\ \frac{\hat{a}_{21}}{\hat{a}_{11}} & 1 \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} \hat{a}_{11} & 0\\ 0 & \hat{a}_{22} \end{bmatrix} \label{eq:6}\]Now, by taking the inverse of the diagonal matrix on the right-hand side, we obtain the ratios as below:

\[\begin{bmatrix} \frac{\hat{b}_{11}}{\hat{a}_{11}} & \frac{\hat{b}_{12}}{\hat{a}_{22}}\\ \frac{\hat{b}_{21}}{\hat{a}_{11}} & \frac{\hat{b}_{22}}{\hat{a}_{22}} \end{bmatrix} = \bs{S}\begin{bmatrix} 1 & \frac{\hat{a}_{12}}{\hat{a}_{22}}\\ \frac{\hat{a}_{21}}{\hat{a}_{11}} & 1 \end{bmatrix} \label{eq:7}\]So now, we define the ratios on the left-hand side of the above equation as the measured S-parameters (this is just a definition). We can then rewrite the remaining ratios on the right-hand side as follows:

\[\begin{bmatrix} \overbar{S}_{11} & \overbar{S}_{12}\\ \overbar{S}_{21} & \overbar{S}_{22} \end{bmatrix} = \bs{S}\begin{bmatrix} 1 & \overbar{S}_{12}\Gamma_{12}\\ \overbar{S}_{21}\Gamma_{21} & 1 \end{bmatrix} \label{eq:8}\]where $\overbar{S}_{ij}$ represents the measured S-parameters and $\Gamma_{ij}$ represents the switch terms:

\[\overbar{S}_{ij} \stackrel{\text{def}}{=} \frac{\hat{b}_{ij}}{\hat{a}_{jj}}, \qquad \Gamma_{ij} \stackrel{\text{def}}{=} \frac{\hat{a}_{ij}}{\hat{b}_{ij}} \label{eq:9}\]The switch terms are formed by the ratios of the receivers of the non-driving port. Therefore, they are independent of the measured DUT, as any influence by the DUT will be seen equally by both waves $\hat{a}_{ij}$ and $\hat{b}_{ij}$. In general, the S-parameters corrected for switch terms are given as follows:

\[\bs{S} = \begin{bmatrix} \overbar{S}_{11} & \overbar{S}_{12}\\ \overbar{S}_{21} & \overbar{S}_{22} \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 1 & \overbar{S}_{12}\Gamma_{12}\\ \overbar{S}_{21}\Gamma_{21} & 1 \end{bmatrix}^{-1} \label{eq:10}\]In the special case where the measured two-port device is transmissionless, the switch terms $\Gamma_{ij}$ have no influence because $\overbar{S}_{21}=\overbar{S}_{12}=0$. In a four-sampler VNA, we can directly measure $\Gamma_{ij}$ by connecting any transmissive device and calculating the ratio according to the definition in \eqref{eq:9}. Note that switch terms are deterministic and can be measured once and reused. Therefore, after computing $\Gamma_{ij}$, you no longer need to use the fourth receiver since $\overbar{S}_{ij}$ can be measured using only three receivers.

Fun fact: The S-parameters measured with most VNAs are, to my knowledge, always defined as ratios, even when this is not the correct definition, as the incident wave of the non-driving port is not zero. This definition is only valid for single port devices. The reason why VNA vendors do this goes back to the reason why they intentionally don’t sample the fourth receiver.

For completeness, below is the structure of switch term corrected N-port S-parameter measurements:

\[\bs{S} = \begin{bmatrix} \overbar{S}_{11} & \overbar{S}_{12} & \overbar{S}_{13} & \cdots &\overbar{S}_{1N} \\ \overbar{S}_{21} & \overbar{S}_{22} & \overbar{S}_{23} & \cdots & \overbar{S}_{2N} \\ \overbar{S}_{31} & \overbar{S}_{32} & \overbar{S}_{33} & \cdots & \overbar{S}_{3N} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\ \overbar{S}_{N1} & \overbar{S}_{N2} & \overbar{S}_{N3} & \cdots & \overbar{S}_{NN} \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 1 & \overbar{S}_{12}\Gamma_{12} & \overbar{S}_{13}\Gamma_{13} & \cdots &\overbar{S}_{1N}\Gamma_{1N} \\ \overbar{S}_{21}\Gamma_{21} & 1 & \overbar{S}_{23}\Gamma_{23} & \cdots & \overbar{S}_{2N}\Gamma_{2N} \\ \overbar{S}_{31}\Gamma_{31} & \overbar{S}_{32}\Gamma_{32} & 1 & \cdots & \overbar{S}_{3N}\Gamma_{3N} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\ \overbar{S}_{N1}\Gamma_{N1} & \overbar{S}_{N2}\Gamma_{N2} & \overbar{S}_{N3}\Gamma_{N3} & \cdots & 1 \end{bmatrix}^{-1} \label{eq:11}\]While there may seem to be a lot of switch terms, there are actually only N unique switch terms. This is because all switch terms in the same matrix row are equal. Since there are N rows, there are N switch terms.

\[\Gamma_{ij} = \Gamma_{ik}, \qquad \text{for all } j\ne k \label{eq:12}\]The reason why switch terms are the same regardless of the excited port is due to the fact that they are reflections caused by physical objects. They are the reflection of the termination load of the port. As long as the termination is not changed during the switching between ports, the switch terms remain the same regardless of the driving port.

Indirect Measurement

Below, I present a new method for indirectly measuring switch terms [1]. This method uses only three receivers of the VNA and a couple of reciprocal devices.

To begin the derivation, we describe a two-port measurement using T-parameters. By defining T-parameters using wave quantities, we arrive at two equations: one for the forward direction and the other for the reverse direction.

\[\begin{bmatrix} \hat{a}_{11}\\\hat{b}_{11} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} T_{11} & T_{12}\\ T_{21} & T_{22} \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} \hat{a}_{21}\\\hat{b}_{21} \end{bmatrix}, \qquad \begin{bmatrix} \hat{a}_{12}\\\hat{b}_{12} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} T_{11} & T_{12}\\ T_{21} & T_{22} \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} \hat{a}_{22}\\\hat{b}_{22} \end{bmatrix} \label{eq:13}\]By combining both results into a single matrix, we get the following:

\[\begin{bmatrix} \hat{a}_{11} & \hat{a}_{12}\\ \hat{b}_{11} & \hat{b}_{12} \end{bmatrix} = \underbrace{\begin{bmatrix} T_{11} & T_{12}\\ T_{21} & T_{22} \end{bmatrix}}_{\bs{T}}\begin{bmatrix} \hat{a}_{21} & \hat{a}_{22}\\ \hat{b}_{21} & \hat{b}_{22} \end{bmatrix} \label{eq:14}\]Now, let’s consider the error box model of a two-port VNA, as depicted in the illustration below. We can replace the matrix $\bs{T}$ in the above equation with the cascade model of the error box model, which gives us the following result:

\[\begin{bmatrix} \hat{a}_{11} & \hat{a}_{12}\\ \hat{b}_{11} & \hat{b}_{12} \end{bmatrix} = \bs{E}_\mathrm{L}\bs{T}_\mathrm{D}\bs{E}_\mathrm{R}\begin{bmatrix} \hat{a}_{21} & \hat{a}_{22}\\ \hat{b}_{21} & \hat{b}_{22} \end{bmatrix} \label{eq:15}\]where $\bs{E}_\mathrm{L}$ and $\bs{E}_\mathrm{R}$ are the left and right error boxes, and $\bs{T}_\mathrm{D}$ is the actual DUT.

Fig. 4. Error box model of a two-port VNA.

Fig. 4. Error box model of a two-port VNA.

Next, the wave parameter matrices are split into a diagonal part and a non-diagonal part.

\[\begin{bmatrix} 1 & \frac{\hat{a}_{12}}{\hat{b}_{12}}\\ \frac{\hat{b}_{11}}{\hat{a}_{11}} & 1 \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} \hat{a}_{11} & 0\\ 0 & \hat{b}_{12} \end{bmatrix} = \bs{E}_\mathrm{L}\bs{T}_\mathrm{D}\bs{E}_\mathrm{R}\begin{bmatrix} \frac{\hat{a}_{21}}{\hat{b}_{21}} & 1\\ 1 & \frac{\hat{b}_{22}}{\hat{a}_{22}} \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} \hat{b}_{21} & 0\\ 0 & \hat{a}_{22} \end{bmatrix} \label{eq:16}\]This simplifies further by multiplying through the inverse of the diagonal matrix on the right-hand side, reducing all wave parameters to ratios:

\[\begin{bmatrix} 1 & \frac{\hat{a}_{12}}{\hat{b}_{12}}\\ \frac{\hat{b}_{11}}{\hat{a}_{11}} & 1 \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} \frac{\hat{a}_{11}}{\hat{b}_{21}} & 0\\ 0 & \frac{\hat{b}_{12}}{\hat{a}_{22}} \end{bmatrix} = \bs{E}_\mathrm{L}\bs{T}_\mathrm{D}\bs{E}_\mathrm{R}\begin{bmatrix} \frac{\hat{a}_{21}}{\hat{b}_{21}} & 1\\ 1 & \frac{\hat{b}_{22}}{\hat{a}_{22}} \end{bmatrix} \label{eq:17}\]The final simplification is to replace the ratios with the definitions established in \eqref{eq:9}. This yields the following expression:

\[\begin{bmatrix} 1 & \Gamma_{12}\\ \overbar{S}_{11} & 1 \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 1/\overbar{S}_{21} & 0\\ 0 & \overbar{S}_{12} \end{bmatrix} = \bs{E}_\mathrm{L}\bs{T}_\mathrm{D}\bs{E}_\mathrm{R}\begin{bmatrix} \Gamma_{21} & 1\\ 1 & \overbar{S}_{22} \end{bmatrix} \label{eq:18}\]Our goal is to extract $\Gamma_{21}$ and $\Gamma_{12}$ without prior knowledge of the error boxes or the DUT. We do this by assuming the DUT is a reciprocal device, which satisfies $\mathrm{det}\left(\bs{T}_\mathrm{D}\right)=1$. Applying the determinant to \eqref{eq:18} and using the property $\mathrm{det}\left(\bs{A}\bs{B}\right)=\mathrm{det}\left(\bs{A}\right)\mathrm{det}\left(\bs{B}\right)$, we arrive at:

\[(1-\overbar{S}_{11}\Gamma_{12})\frac{\overbar{S}_{12}}{\overbar{S}_{21}} = \underbrace{\mathrm{det}\left(\bs{E}_\mathrm{L}\right)\mathrm{det}\left(\bs{E}_\mathrm{R}\right)}_{c}(\Gamma_{21}\overbar{S}_{22}-1) \label{eq:19}\]The above expression can be simplified as follows:

\[\frac{\overbar{S}_{12}}{\overbar{S}_{21}}-\overbar{S}_{11}\frac{\overbar{S}_{12}}{\overbar{S}_{21}}\Gamma_{12} -\overbar{S}_{22}c\Gamma_{21} + c = 0 \label{eq:20}\]From the above equation we can see that we have a linear equation in three unknowns: $\Gamma_{12}$, $c\Gamma_{21}$, and $c$. Therefore, measuring at least three unique transmissive reciprocal devices lets us solve by forming the following linear system:

\[\begin{bmatrix} -\overbar{S}_{11}^{(1)}\frac{\overbar{S}_{12}^{(1)}}{\overbar{S}_{21}^{(1)}} & -\overbar{S}_{22}^{(1)} & 1 & \frac{\overbar{S}_{12}^{(1)}}{\overbar{S}_{21}^{(1)}}\\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots\\ -\overbar{S}_{11}^{(M)}\frac{\overbar{S}_{12}^{(M)}}{\overbar{S}_{21}^{(M)}} & -\overbar{S}_{22}^{(M)} & 1 & \frac{\overbar{S}_{12}^{(M)}}{\overbar{S}_{21}^{(M)}} \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} \Gamma_{12}\\ c\Gamma_{21}\\ c\\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \bs{0} \label{eq:21}\]Here, $M\geq 3$ represents the number of measured reciprocal devices. We need at least three unique measurements to solve for the unknowns, as the system matrix must have a rank of 3 to be solvable. To solve for the unknowns, we must find the nullspace of the system matrix. This can be computed through singular value decomposition (SVD), where the best approximation of the nullspace corresponds to the right singular vector that corresponds to the smallest singular value. Since the nullspace is only unique up to a scalar multiple, we can solve for the switch terms by taking the ratio of the elements of the nullspace vector as follows:

\[\Gamma_{12} = \frac{v_{41}}{v_{44}}, \qquad \Gamma_{21} = \frac{v_{42}}{v_{43}} \label{eq:22}\]where $\bs{v}_{4} = [v_{41}, v_{42}, v_{43}, v_{44}]^T$ is the nullspace vector found through the SVD.

When selecting reciprocal devices, there are a few things to keep in mind. First, remember that we can only solve for the switch terms if the system matrix above has sufficient rank. If you choose devices that have similar frequency responses, you will get a poor estimation of the switch terms. For instance, it’s not advisable to use two transmission lines, as they may have similar phase at certain frequencies. Instead, opt for series resistive loads, which are reciprocal and have dissimilar frequency responses. You can use one thru and two series resistors (e.g., 50 and 100 ohm). Don’t be concerned about the frequency response of the resistors not being ideal, as long as they are different and reciprocal (transmissive), it should work.

You can check my GitHub repository for measurements and comparisons between the direct and indirect methods of measuring switch terms: https://github.com/ZiadHatab/vna-switch-terms

References

[1] Z. Hatab, M. E. Gadringer and W. Bösch, “Indirect Measurement of Switch Terms of a Vector Network Analyzer with Reciprocal Devices,” in IEEE Microwave and Wireless Technology Letters, 2023, doi: 10.1109/LMWT.2023.3311032, e-print doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2306.07066.

[2] R. B. Marks, “Formulations of the Basic Vector Network Analyzer Error Model including Switch-Terms,” 50th ARFTG Conference Digest, 1997, pp. 115-126, doi: 10.1109/ARFTG.1997.327265.